“An old house is slowly moved from its land, the grain of its wooden pillars breathing with generations of memories.”

“一座老屋缓缓被迁离原地,木柱的纹理里藏着三代人的呼吸与故事。”

My documentary takes the relocation of a Mosuo mother house in Walabi Village, Lugu Lake, as an ethnographic lens to explore the intersection of gender, tradition, and space in a matrilineal society. Through intimate observation and interviews with three generations—-Ama, Aqi, and Nicima, the film examines how the mother house functions as both a physical dwelling and a material embodiment of lineage and identity. By documenting the process of relocation, the director reveals how traditional culture is reinterpreted and reshaped amid modernization, reflecting the ongoing reconstruction of matrilineal values in contemporary contexts.

这部纪录片以云南泸沽湖瓦拉壁村摩梭人的祖母屋搬迁为研究起点,聚焦母系社会中女性角色与家屋文化的关系。影片通过对三代人—-阿妈、阿七尼次玛、格桑拉姆。的观察与访谈,揭示家屋在身份认同、权力结构与文化传承中的多重意义。祖母屋不仅是生活空间,更是族群记忆的物质化形式。通过记录这一迁移过程,导演呈现了传统文化在现代化冲击下的再生产与转化,探讨母系社会在当代语境中的延续与重构。

The story began with curiosity.

故事的开始源于好奇。

At first, I went to Lugu Lake to learn about the Mosuo’s unique walking marriage, a tradition both tender and complex.

But during my visits, I heard that a family was preparing to relocate their mother house.

That moment changed everything.

The focus shifted from marriage to the home itself—- from relationships between people to the spaces that hold those relationships.

I realized that the mother house is more than wood and earth; it breathes, remembers, and shelters generations of women.

起初我前往泸沽湖,是想了解摩梭人独特的“走婚”制度,那是一种温柔又复杂的传统。

可在走访的过程中,我偶然得知有一户人家正准备搬迁他们的祖母屋。

那一刻,一切都改变了。

我的视角从婚姻转向家屋—-从人与人之间的关系,转向承载这些关系的空间。

我逐渐意识到,祖母屋不只是木与土的结合,它有呼吸,有记忆,庇护着一代又一代的女性。

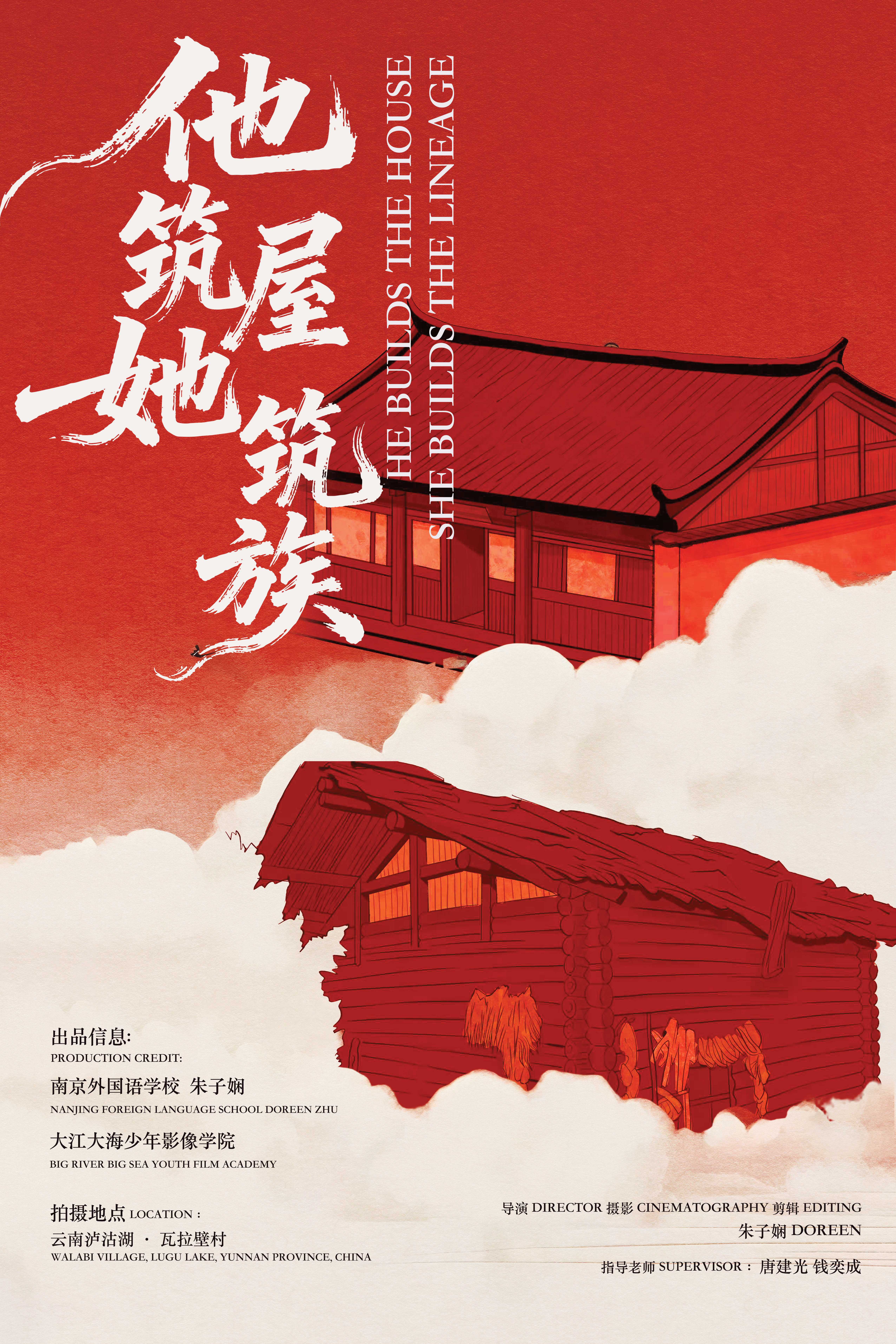

He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage.

他筑屋,她筑族

Director‘s statement

导演自述

The documentary originated from my ethnographic fieldwork on the Mosuo walking marriage system.

But during my visits, I heard that they were moving their mother house — something that happens among the Mosuo only once in centuries.

I knew it was a moment worth documenting, because it wasn’t just a relocation — it was culture in motion.

这部纪录片的灵感源于我对摩梭“走婚”制度的研究。

可在走访的过程中,我听说她们要搬迁祖母屋—-那是对于摩挲人来说几百年才会发生一次的事。

我知道那一刻值得被记录,因为那不仅是一场搬迁,而是一种文化在流动。

I arrived at Lugu Lake, Yunnan, marking the start of my filming journey. The weather changed constantly, but the calm of the lake helped me settle into fieldwork. I spent the first day getting to know the surroundings and observing the daily rhythm of the village.

我抵达云南泸沽湖,正式开始纪录片拍摄。一路上天气多变,但泸沽湖的宁静让我很快进入了田野的状态。我花了一天时间熟悉环境,观察村落的布局与生活节奏。

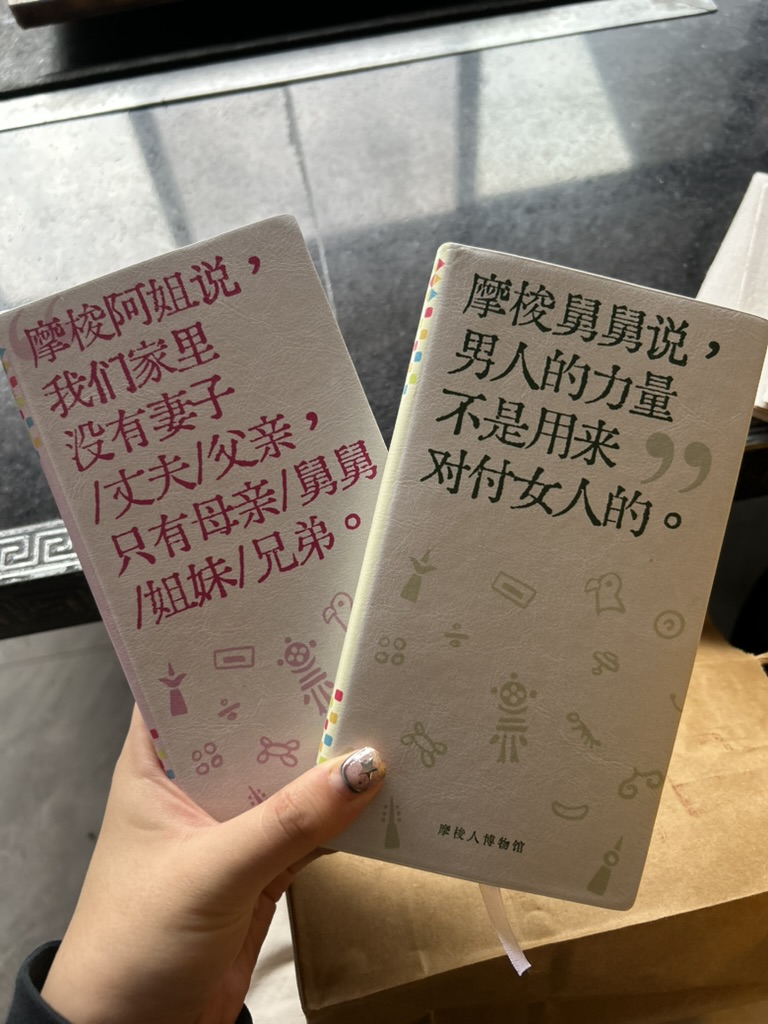

I visited the Mosuo Museum to learn about the walking marriage system and their matrilineal social structure. It gave me an initial understanding of Mosuo life and made me reflect on the role of women in family and culture.

我参观了摩梭人博物馆,了解了“走婚”制度和母系社会的结构。这让我对摩梭人的生活方式有了初步认识,也让我思考女性在家庭与文化中的位置。

I visited Aqi’s home and met his and his mother, Ama, for the first time. They told me their family would soon relocate their mother house—something that might happen only once in centuries among the Mosuo. After hearing this, I immediately decided to shift the focus of my documentary to capture this rare moment.

我前往阿七家进行走访,与他和他的母亲阿妈第一次见面。她们告诉我,家里即将搬迁祖母屋,而这种情况在摩梭社会中可能几百年才会发生一次。听到这里,我立刻决定改变拍摄主题,记录下这个珍贵的时刻。

That day, Aqi’s family began dismantling the old mother house. I filmed the whole process—from removing the pillars to clearing the roof tiles. The family members joined to help, and the atmosphere was both solemn and emotional; their respect for the house was deeply moving.

这一天,阿七家正式开始拆旧的祖母屋。我拍摄了整个过程,从卸下木柱到清理瓦片。家族成员都来帮忙,气氛紧张又庄重,我能感受到他们对祖母屋深深的敬意。

I organized the footage and completed the first rough cut.

我整理了前几天的素材,并进行了第一版粗剪。

The Daba, a local shaman, chose this day to perform the ritual for the new mother house. I filmed the entire process—from chanting and lighting the fire to the first communal meal. At noon, we shared a traditional Mosuo feast; everyone called it a “blessing for the new house.”

达巴选择了这天为新祖母屋举行仪式。我拍下了诵经、点火和会客的全过程,整场仪式持续了数小时。中午,我们一起吃了摩梭民族餐,大家都说这是一种“新屋的祝福”。

In the morning, I conducted in-depth interviews with Aqi and Ama about their plans and feelings toward the new house. They spoke about home, inheritance, and the meaning of continuity. In the afternoon, I suggested Aqi take her daughter GesangLamu to visit the old house in the mountains—the scene of three generations together became one of the most touching moments of the film.

上午,我对阿七和阿妈进行了深入采访,了解她们对新屋的想法和计划。她们谈到了家、传承与未来的意义。下午,我建议让阿七带女儿格桑拉姆去山上的老屋看看,三代人的画面成了纪录片中最打动我的一段。

My supervisor and I started editing the A and B rolls. We carefully selected each shot and refined the pacing to let the story flow naturally. We worked late into the night, but seeing the film gradually take shape made all the fatigue worth it.

我和我的老师开始剪辑 A row 和 B row。我们仔细挑选每一段素材,反复调整节奏,让故事更自然流动。每天剪到深夜,但看到片段逐渐成形,疲惫都变成了成就感。

I finished the final edit, marking the end of the project. Reviewing the footage, I felt a quiet sense of fulfillment. Though the filming had ended, the story of the mother house will keep living in my memory.

我完成了最后一次精剪,这也意味着整个拍摄旅程的结束。回看素材时,我感到一种安静的满足。虽然纪录片结束了,但祖母屋的故事,会在我心里继续延伸。

Mosuo Ancestral House and Culture

摩梭祖屋与文化

History and Cultural Heritage

历史与文化传承

The Mosuo live in the highlands between Yunnan and Sichuan, among the few remaining matrilineal societies in the world. The structure, rituals, and daily life of the mother house form the foundation of Mosuo “house culture.” Despite modernization and tourism, its essence remains centered on matrilineal inheritance and women’s strength. Construction and relocation of a mother house follow traditional ceremonies symbolizing renewal, each relocation reaffirming collective memory.

摩梭人生活在云南与四川交界的高原地带,是世界上少数保留母系血缘体系的民族之一。祖母屋的结构、仪式与生活共同构成摩梭的“家屋文化”。虽受现代化与旅游影响,其核心仍是母系传承与女性力量。祖母屋的修建与搬迁遵循传统仪式,象征文化延续。每一次搬迁,都是族群记忆的再确认。

The Hearth

火塘

Located at the center of the mother house, the hearth is the core of family life. Cooking, warmth, gatherings, and rituals all take place here. Its fire symbolizes life and lineage and is never allowed to go out. The hearth layout reflects gendered space: men sit closer to the interior, women near the entrance, showing order and respect. The three stones beneath the fire are known as the “Three Hearth Gods,” symbolizing protection from ancestors and nature.

位于祖母屋中心,是家族生活的核心。烹饪、取暖、聚餐、祭祀都在这里进行。火焰象征生命与血脉的延续,从不轻易熄灭。火塘的布局反映性别空间:男性坐在内侧,女性靠近外侧,体现家庭秩序与尊重。火塘的三块石头被称为“火塘三神”,象征祖先与自然的守护。

Male and Female Pillars

男柱与女柱

Two main wooden pillars, the male and female pillars, stand inside the house. They support the beams structurally and symbolize gender balance and household stability. During rituals, family members touch them for blessings of strength and continuity. The male pillar stands closer to the hearth’s inner side, the female near the door—forming a yin-yang symmetry that represents the Mosuo belief in gender harmony.

屋内竖立两根主柱,称为男柱与女柱。结构上支撑屋梁,象征男女平衡与家族稳定。仪式中人们会触摸木柱祈福,祈求力量与延续。男柱靠火塘内侧,女柱靠外门,形成阴阳对位。它们体现了摩梭人“和谐共生”的性别观。

Gate of Life and Death

生死门

The main doorway, called the “Gate of Life and Death,” marks the boundary between the home and the outside world. One must bow slightly when entering as a gesture of respect. The Mosuo believe that the inside belongs to ancestors and order, while the outside represents the secular world. A sheep or ox skull is often hung above the door to ward off evil. The doorway’s height and design embody the dignity and unity of the family.

祖母屋的大门被称为“生死门”,象征家与外界的界限。进屋须低头,表示尊敬与谦卑。摩梭人认为门内属于祖先与秩序的空间,门外是俗世与混乱。门上常悬挂羊头或牛头以驱邪祈福。门框高度和形制象征家族尊严与凝聚。

Sheep Head and Murals

羊头与壁画

A sheep head hung above the door symbolizes protection and prosperity, representing strength and sacrifice. Inside, thangka paintings or Buddhist murals serve for blessing and ancestor remembrance. The imagery blends Tibetan Buddhism with Mosuo folk beliefs, reflecting the coexistence of faith and everyday life. Motifs of mountains, water, and flowers signify nature and the cycle of life.

羊头悬挂在门上方,象征守护与繁盛,寓意力量与牺牲。屋内常绘唐卡与佛教壁画,用于祈福与纪念祖先。画面融合藏传佛教与摩梭本土信仰,展现宗教与生活的共生。壁画中的山、水、花等图案象征自然与生命循环。

Architectural Layout

建筑布局

The Mosuo mother house is a timber structure, with the courtyard arranged in a square or enclosed layout. The main house sits at the center for women and the family core, while men’s rooms occupy the sides. Slanted roofs protect from rain and snow, and wooden walls reflect plateau craftsmanship. The spatial plan mirrors matrilineal order: the hearth is communal, bedrooms belong to mothers and children, and the ritual area is used for ancestor worship.

摩梭祖母屋为木质结构,院落呈“回”字形或“田”字形布局。主屋位于中央,为女性与家族核心生活区;男性居于边屋。屋顶倾斜以防雨雪,木板墙体现高原气候下的自给设计。空间分布体现母系秩序:火塘为公共中心,卧室属母亲与子女,仪式空间用于祭祖。

Walking Marriage

母系社会中的“走婚”

- The Mosuo practice of walking marriage (Chinese: zou hun) involves men visiting women’s households at night while maintaining residence in their own maternal homes during the day.

- In this system, couples do not traditionally form a resided marital household; children remain in the mother’s house and maternal family raises them.

- The walking-marriage reflects matrilineal descent and the central role of women in household leadership, reinforcing the significance of the mother house as the nucleus of family life.

- 摩梭人所称的“走婚”是男女白天各居其母屋,夜间男方可受邀至女方屋过夜的一种亲密关系。

- 在这种关系中,双方通常不组成传统意义上的婚姻家庭,男方返回自己的母家,女方继续留在母家,孩子由母系家庭抚养。

- 走婚制度体现了母系血缘传承与女性居家主导的社会结构,也强化了家屋(mother house)作为母系家庭核心空间的意义。

Family Structure

家庭结构

- Mosuo family structure is matrilineal: property and household names are passed through the mother’s line, and children reside in the mother’s household (the mother house).

- Household leadership often lies with an elder female (grandmother or mother) who manages the mother house and its affairs.

- While men perform tasks such as livestock or construction, women dominate decision-making, child-rearing and inheritance. The maternal uncle often assumes the father-figure role in the family.

- 摩梭社会以母系血缘为主:家产、家名沿母亲一系传承,子女居住于祖母屋内。

- 在一个母系家屋中,通常由年长女性(如祖母或母亲)为家长,她负责家屋及日常事务管理。

- 男性虽有劳动分工如畜牧或建筑,但家庭决策、子女抚养、家屋继承以女性系为中心;男方角色多为母系兄弟(叔)承担子女监护。

Ritual Traditions

礼仪传统

- Mosuo ritual traditions include coming-of-age ceremonies, ancestor worship, hearth rituals and house-relocation ceremonies. The coming-of-age ceremony is among the most significant cultural events.

- The mother house and its hearth and courtyard space serve both daily life and ritual functions, linking architecture and ceremony.

- 摩梭人在生命阶段(如成年、成人仪式)、祭祖、火塘礼、迁屋仪式中展现其文化系统。例如“成年仪式”被视为极其重要的社会事件。

- 家屋内的公共空间及火塘等结构,不仅是日常生活场域,也是礼仪举办之地,空间与仪式相互关联。

Religious Culture

宗教文化

- The Mosuo’s traditional religion is called Daba—an animistic and shamanistic belief system centered on ancestor worship and spirit rituals.

- In the Daba religion, the ritual specialists known as Daba (priests) operate without formal temples or canonical texts; ceremonies are orally transmitted and used for blessings, exorcisms, naming, and the like.

- The Mosuo also practice Tibetan Buddhism, particularly the Gelugpa school, which has become increasingly influential in their spiritual life.

- Many mother houses have Buddhist statues or thangka paintings; daily life weaves together Daba rituals and Buddhist prayers as part of one living tradition.

- Major life-cycle events—such as naming ceremonies, coming-of-age rituals, and funerals—are often officiated by a Daba or a lama, reflecting how religion permeates both everyday life and major rites of passage.

- 摩梭人的传统宗教称为 达巴教(Daba),是一种以萨满‐巫术和祖先崇拜为核心的信仰体系。

- 在达巴教中,祭司称为“达巴”,他们没有固定的寺院或经典,仪式往往口传进行,服务于祈福、驱邪、命名等重要场合。

- 此外,摩梭人也信奉 藏传佛教,尤其是格鲁派(Gelugpa)佛教在其社会中影响日益显著。

- 家中的祖母屋(mother house)经常配有佛像或藏传佛教的壁画,日常生活中既有达巴教的仪式,也有佛教的祈祷与观念。

Behind the Scenes

幕后故事

Aqi said he grew up in the light of the hearth fire and that one day he would watch his own daughter grow up under the same glow.

When I first saw them lifting the wooden beams of the mother house, I could hardly make a sound. There was a solemn rhythm to it. Everyone knew what to do. No one gave orders and no one complained. The sound of wood rubbing against wood mixed with the wind as if the whole mountain were watching. At that moment I felt very small and very lucky to be allowed to come close to a culture like this and to be trusted to record it.

During the filming I often felt a deep sense of respect. Their rhythm of life was untouched by the outside world. I admire Aqi for continuing his culture and I admire the small steady flames that keep a community alive.

In college I hope to keep finding new ways to understand the world, to listen, to record, and to respect.

The title He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage came from something I felt deeply while filming in Walabi Village.

During the relocation of the mother house, the men lifted beams, stacked walls, and shaped the roof, while the women tended the hearth, prepared food

I realized that “he” and “she” were never opposites, but two forces that sustain the same lineage.

He builds the form of the house; she builds the life within it.

The title became a symbol of cooperation, continuity, and balance.

阿七说,他从小就在火塘的火光下长大,也会在同样的光下看着自己的女儿长大。 当我第一次看见她们搬动祖母屋的木梁时,我几乎不敢出声。那是一种庄严的节奏。每个人都知道自己该做什么,不需要指令,也没有抱怨。木头的摩擦声混着风声,好像整个山都在见证这一刻。那一瞬间,我突然觉得自己非常渺小,也非常幸运:能够被允许靠近这样的文化,被信任去记录它。在拍摄的过程中,我常常感到一种敬畏。她们的生活节奏不被外界定义。我尊敬阿七这样延续文化的人,也尊敬那些看似微小、却支撑了整个族群的火光。因为我希望自己在大学生活可以继续用不同的方式去理解世界,去倾听、去记录、去尊重。

我为我的纪录片起名为《他筑屋,她筑族(He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage)》,来自我在瓦拉壁村的一个真实感受。

在祖母屋的搬迁过程中,男性负责搬梁、垒墙、搭屋顶,而女性则在火塘边守着族人的节奏,安排仪式、准备食物……

那一幕让我意识到,“他”与“她”并不是对立的存在,而是一个家族得以延续的双重力量。

他筑起屋的形体,她延续了家的灵魂。

这部纪录片的名字,也因此成为一种象征——关于合作、传承与平衡。

The poster for He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage was inspired by the relocation of a grandmother’s house. In the scene, Mosuo men and women stand side by side on the eaves of the old grandmother’s house, gazing into the distance where a new one is being built. Their posture of standing together symbolizes the Mosuo tradition of gender equality and cooperation between men and women. Their gaze toward the newly constructed grandmother’s house represents the Mosuo people’s hope and aspiration for a better future. The symbolic meaning embodied in this moment forms the core inspiration for my poster design.

《他筑屋,她筑族He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage 》海报灵感来源于这场关于祖母屋的搬迁。摩梭男女并肩站立在旧祖母屋的屋檐上向远方眺望,而远方是他们即将建成的新祖母屋。男女并肩姿态寓意着摩梭族男女平等,分工合作的传统。他们注视着远方兴建的新祖母屋则是摩梭人对未来生活的美好向往以及期盼。这一情景所承载的象征意义,构成了我创作海报的核心灵感来源。

Media and Commentary

媒体与评论

Sherry Lu

This short documentary feels like a piece of prose to me. Though seemingly unassuming, it leaves a profound and lingering resonance. The grandmother’s house portrayed here transcends an ordinary dwelling, embodying instead a selfless sanctuary for a lineage. I believe this documentary resonates so deeply because of the powerful synergy between its fitting music, carefully chosen camera angles, and the editing that seamlessly weaves into the narrative.

这个短纪录片给我的感觉就像一篇散文。虽然看上去平平淡淡,但是有浓重且深邃的回味。祖母屋在这个短片中给人的感觉超出了普通的房子,而是作为一种对一条血脉的无私的庇护。我想这个纪录片可以给人带来强烈的共鸣,是因为合适的音乐、精心挑选的画面角度、和最后融入叙事的剪辑共同带来的效果。

Frank Zhai

The documentary offers an opportunity for audience to experience the Mosuo people’s living and their unique traditions at the shores of Lugu Lake in Yunnan. After understanding meanings of those key elements like old-grandmother‘s house through interviews and descriptions of daily life, I experienced a fantastic documentary which closely present the life of a matrilineal society but a passed down culture.

The relocation of a Mosuo community is the key story here. Due to economic challenges, the leader determined to design cultural heritage projects to attract more tourists. However, they had to dismantle their old grandmother‘s house in order to do so because of limited space. I was deeply moved when the clan leader recalled how she had carried the building materials — mainly wood — “basket by basket” from the mountain. To her, her old grandmother‘s house is a place that had carried her 62-year memories and spirits of generations. Her words, filled with sadness, made me realize that the house was not just a physical shelter but also the spiritual anchor of her people, which is significantly different from our urban lifestyle.

Another striking moment came when a villager spoke about the newly built grandmother’s house. His awkward expressions revealed a loss: many traditions such as eating together or holding rituals would no longer take place in the newly built grandmother‘s house, since it seemed to lack the soul that once bound the community together, and now their lifestyles are continuously disturbed by travelers. The film captures this struggle vividly, showing the tension between preserving cultural heritage and adapting to the demands of modern survival.

What impressed me most, however, was the recurring sound of hammers striking wood in the background. Besides representing the progress of construction, the sound also symbolize as an alarm that valuable cultures like Mosuo culture is at risk in modern times, reminding us to pay more attention to the preservation of their traditions.

Overall, the documentary succeeded in providing authenticity and emotional depth to audience, which largely captures their feelings. After watching it, I admired their determination to find ways to protect their traditions, but I feel concerned about their predicament. As a reflection, the documentary is a vary thought-provoking work which invites viewers to reflect on the balance between cultural preservation and modernization.

这部纪录片把镜头对准了云南泸沽湖畔的摩梭人,让观众有机会真正走进他们的日常生活,感受一个母系社会独特而古老的传统文化。通过采访与日常生活的记录,“祖母房”等重要文化符号变得鲜活而具体。

影片讲述了一个以摩梭族搬迁祖母房为核心故事。由于经济上的压力,族长决定通过打造非遗文化项目来吸引游客。然而受制于有限的空间,他们不得不拆掉世代居住的祖母房。让我印象最深的,是族长在采访中提到,当年建房时,她是如何“一筐一筐”把材料从山上背下来的。她眼神里的无奈与声音里的沉重,让我明白祖母房对她而言,早已超越了一栋房子的意义,它是家族的精神依托,也是凝聚几代人记忆的象征。

纪录片中还呈现了新旧转换带来的矛盾。当有族人谈到新建的祖母房时,那种尴尬和犹疑的表情让我感受到一种说不清的失落。新的房子虽然更坚固,但许多传统习俗——比如在祖母房里一起吃饭、举行祭祀——却正在慢慢消失。看似换来了“发展”,实则失去了原本的灵魂。影片在这一点上展现得非常真实,也让人感受到他们在保护传统与迎合现实之间的挣扎。

让我久久难忘的,还有贯穿片子的锤子声。那清脆的“铛铛铛”既是修建新屋的节奏声,又像是一记警钟。它提醒我们,这样珍贵的文化正在悄然发生改变,甚至面临消亡的危险。对摩梭人来说,这是沉重的现实;对我们观众来说,更是一个关于关注与保护的呼唤。

整体来看,这部纪录片真实而有力量。它没有浮夸的叙事,却通过细腻的镜头和真挚的情感,把摩梭人在文化与生存之间的矛盾刻画得淋漓尽致。观影之后,我既为他们的坚持感到敬佩,也为他们的无奈而深深叹息。这是一部发人深省的作品,它让人思考,现代化的进程中,我们到底该如何守护那些正在逐渐消逝的文化传统。

Jessie Yu

Set against the backdrop of Walabi Village in Yunnan’s Ninglang Yi Autonomous County, He Builds the House, She Builds the Lineage offers a quiet but profound look into the reconstruction of homes—and far more than that.

Using housing reconstruction as a lens, the documentary invites viewers deep into the traditions, rituals, and human relationships of an ethnic community. In the act of rebuilding, we witness attachment to land, intergenerational collaboration, and the subtle reshaping of heritage under the weight of modernity.

What truly stands out is the film’s creative soundscape: the rhythmic hammering, the friction of timber, the pulse of labor, all composed into a cadence so musical it feels like the land itself is singing. This auditory language elevates them, turning construction into something intimate, almost sacred.

Without grand declarations or didactic framing, this documentary builds a quiet bridge between past and future, people and place, structure and spirit.

在群山环绕的云南宁蒗彝族自治县瓦拉壁村,一场静悄悄却意义深远的重建正在发生。《他筑屋,她筑族》用平视的镜头与诗意的节奏,记录了少数民族家庭的选择与坚守。

影片以房屋重建为媒介,带领观众深入一个民族的文化与习俗,体察人情的细腻与坚韧。通过建房这一具体的行动,我们看见了族群对土地的依恋、家庭之间的合作,以及传统生活方式在现代化浪潮中的再生与转化。

最令人动容的,是影片对声音的运用:锤子落下的节奏、木头碰撞的声响,交织成一种异域旋律,仿佛是这片土地自己在唱歌。这种创意性的音响设计,不仅增强了沉浸感,也让观众听见了“建房”这件事的尊严与温柔。

这部纪录片没有宏大的宣言,也没有说教式的框架,而是在过去与未来、人与地方、结构与精神之间架起了一座静谧的桥梁。

Copyright and Acknowledgements

版权与致谢

特别鸣谢:

瓦拉壁村摩梭手工工坊

云南摩梭人博物馆

阿七尼次玛一家

感谢他们在拍摄期间敞开家门,分享生活与信任。

大江大海少年影像学院

唐建光老师

钱奕成老师

感谢他们在创作过程中给予的专业指导与精神支持。

我的妈妈孙小美及她的挚友们

感谢她们在我云南拍摄期间提供的后勤支持与温暖陪伴。

以及所有观看纪录片并分享反馈的观众

你们的每一句话,都让我看到纪录片真正抵达的意义。

谨以此片,致敬所有为摩梭文化延续而努力的人!

Special Thanks

Walabi Village Mosuo Handicraft Workshop

Yunnan Mosuo Museum

Aqi Nicima’s Family

for opening their home and sharing their lives and trust.

Da Jiang Da Hai Youth Film Academy

Mr. Tang Jianguang

Mr. Qian Yicheng

for their professional guidance and generous support throughout the filmmaking process.

My mother, Ms. Sun Xiaomei, and her dear friends

for their heartfelt care and logistical support during my filming journey in Yunnan.

And to all the viewers who have watched and shared their reflections

your words remind me the significance of documentary.

This film is dedicated to all those who strive to preserve and record the living culture of the Mosuo people!